A Seamless Global Terrain Model in the Hipparchus System

Hrvoje Lukatela,

Geodyssey Limited

http://www.geodyssey.com/

Paper presented at the International Conference on Discrete Global Grids,

Santa Barbara, 26 - 28 March 2000

Abstract

This paper outlines the steps used to construct seamless global

triangular networks similar to the planar TIN commonly used to

facilitate terrain modeling and volumetrics. It is based on global

coordinates and a planetary surface tessellation using spheroidal

Voronoi polygons. The techniques used to extend the surface modeling

across the Voronoi cell boundaries are presented. The paper also outlines

the strategy used for the efficient retrieval of only those parts of the

model that are visible in a transient view, as well as the platform- and

projection-independent approach to surface rendering.

Introduction

Representation of the physical surface of the Earth in digital

systems is a subject of considerable current attention. As the area of

the coverage of such systems increases, it becomes necessary to provide

methods to model very large, continuous surface conglomerates in a manner

which does not violate the surface integrity (i.e., which does not impose

hard partitioning as an artifact of the digital model), but, at the same

time, provides an efficient spatial index to a small section of the surface

of transient interest.

Representation of the physical surface of the Earth in digital

systems is a subject of considerable current attention. As the area of

the coverage of such systems increases, it becomes necessary to provide

methods to model very large, continuous surface conglomerates in a manner

which does not violate the surface integrity (i.e., which does not impose

hard partitioning as an artifact of the digital model), but, at the same

time, provides an efficient spatial index to a small section of the surface

of transient interest.

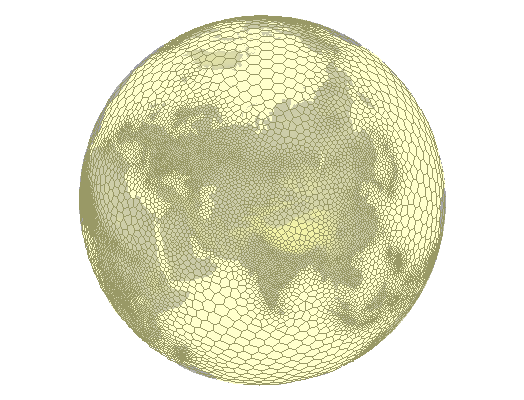

Figure 1: A "global grid" of Voronoi polygons

The Hipparchus Geopositioning Model

(outlined in considerable detail in a web-resident publication titled:

Hipparchus Geopositioning Model: an Overview)

provides a method of construction and manipulation of geometric objects

of various levels of complexity (points, lines, areas and surfaces)

in a manner which imposes no restrictions on their spatial size or

shape. The system is based on two major computational geometry constructs:

use of the vector components of the ellipsoid normal instead of the latitude

and longitude angles and data-density driven tessellation of the planetary

surface using a global grid of spheroidal Voronoi polygons.

The position of a point on the surface of the ellipsoid is best given

by a numerical definition of the normal to the surface at that point.

The common global coordinates - latitude and longitude - are angles:

the first of the two is between the normal and the Equatorial plane

and the second between the Equatorial plane projections of the normal and

the projection of the prime meridian. Traditional geodetic computations

(for instance: given are two known points, determine the length and the

azimuth of the shortest line that connects them...) are based on

trigonometric functions of those angles and on the expansion of the power

series of the eccentricity of the ellipsoid. The angles, however, present

two problems when used for computations on digital computers: transcendental

functions (sines, cosines) require many more CPU cycles than the algebraic

primitives (addition, multiplication) and their areas of singularity must

be compensated with complicated and error-prone code. Thus replacing angles

with vector components of the ellipsoid normal was noticed as potentially

beneficial as soon as the digital computers were incorporated into the

geodetic practice (cf. Bomford (1975), remark on formulae "symmetrical and

better for computation...", p. 593 - under 'Cartesian Coordinates in

Three Dimensions'). Hipparchus computations are consistently based on

the ellipsoid normal given by its vector components instead of the latitude

and longitude angles.

A "global grid" is, in the most general sense, a geometrical subdivision

of the planetary surface which assists in the organization (partitioning,

indexing, etc.) of globally-distributed digital data. "Regularity" of

the grid usually translates to simple data structures and straightforward

classification algorithms. Since no regular and isometric tessellation of

the sphere (beyond five platonic solids) is possible, practical applications

have two alternatives: to retain in the design of the "grid" as much

"regularity" as possible, to be rewarded with a considerable algorithmic

elegance, but at the expense of the ability to perform fast and accurate

geodetic computations (see Dutton, (1999) for a well-known example of such

approach), or to accept the "irregular" nature of the grid while attempting

to make computations based on it as fast and as precise as possible.

The Hipparchus system makes no attempt to produce a "regular" grid. Instead, the

grid is designed so that any particular implementation of the grid can match

the density of the data that inhabits it and so that the parameters which

numerically define the grid "cells" assist (and not hinder) the speed and

precision of geodetic computations and spatial algebra productions.

(Figure 1 shows a sample of such grid with the density derived from the

density of the human population). It is based on the surface subdivision

known as "Voronoi polygons": a purposefully selected finite and discrete

set of "cell-center" points subdivides the surface so that any surface point

is uniquely associated (i.e., it "belongs to") the member of the set that

it is closest to. The point classification is accomplished using only

distance calculations. Point, line, area and surface object sets are in

turn defined in terms of the cells they occupy and the vertex coordinates,

represented not by a the full (global) vector representation of the

ellipsoid normals, but by the vector difference from their respective

cell center points. An extended introduction to and computational geometry

treatment of the Voronoi polygons can be found in O'Rourke (1994).

This paper outlines the canonical representation of the surface object,

and explores the techniques which are used to operate upon it.

While the context and the examples used in this paper center on the

representation of the terrain, such objects can be used to represent

any continuous function for which a sufficiently dense set of point-location

dependent scalar values are known, and about which we know enough to

postulate that each planetary surface point will have one (and only one)

measured or interpolated function value.

Triangulated Irregular Network - TIN

The triangulated irregular network (TIN) is an often used surface

representation method in planar computational geometry. Description of TIN

data structures and the algorithms (including C language source code)

can be found in both Ambroziak (1993) and Lischinski (1994). The TIN

approximates a continuous surface with a mesh of triangles which

more or less coincide with it. The quality of this approximation depends

on the combination of the method by which the elevation measurement

points have been selected, and the triangulation strategy.

The implementation described herein assumes a more-or-less uniform

density of significant points and starts with a simple "least-diagonals"

fast iterative planar triangulation algorithm. It is open to accept

different triangulation strategies - presumably matching more closely

the peculiarities of the input data generation process.

The triangulated irregular network (TIN) is an often used surface

representation method in planar computational geometry. Description of TIN

data structures and the algorithms (including C language source code)

can be found in both Ambroziak (1993) and Lischinski (1994). The TIN

approximates a continuous surface with a mesh of triangles which

more or less coincide with it. The quality of this approximation depends

on the combination of the method by which the elevation measurement

points have been selected, and the triangulation strategy.

The implementation described herein assumes a more-or-less uniform

density of significant points and starts with a simple "least-diagonals"

fast iterative planar triangulation algorithm. It is open to accept

different triangulation strategies - presumably matching more closely

the peculiarities of the input data generation process.

The data structure used to represent a planar TIN is simple and

shows only minor variations from one implementation to another.

It consists conceptually of an array of points and an array of

triangles. The two may be doubly linked, but commonly only

the triangles are linked to their vertices. Additionally, each

triangle is linked to its three neighbors, with a flag value

to signal that a triangle edge is at the same time the edge of the

TIN (i.e., it is an "outside" edge). Most triangulation algorithms

produce a structure in which all outer edges form a planar convex hull.

A point array element consists of planar coordinates and elevation.

If the shading or perspective rendering is anticipated, triangle

normals might be included in the data; this however would be worthwhile

only if the cost of re-computing the triangle orientation far outweighs

the cost of additional storage and, usually of even greater significance,

the time required to access it.

The main difficulty in the implementation of computational geometry

algorithms usually stems from the need to properly predict all (or at

least all likely) degeneracy and singularity cases. (See in particular

comments under "Robustness" in Lischinski (1994)). While the implementation

described in this paper is no exception, it is interesting to note that

all such problems were encountered (and hopefully resolved) in the planar

("in-cell") geometry domain.

A TIN in a Global Voronoi Grid

In general, the Voronoi polygon grid used to model the TIN will be used

to provide the spatial framework for a number of other object classes.

The only requirement that the implementation of TIN data will place on the

grid is that the density of the elevation points remains approximately an

order of magnitude above the density of the Voronoi polygon centers.

In this - and a number of other characteristics - a TIN object in a global

Voronoi grid parallels the combined characteristics of Hipparchus point

and line sets. This TIN will additionally consist simultaneously of two

levels of triangle/elevation data: high-volume triangles with source data

points as their vertices and low-volume, large triangles with cell-center

and end-points of cell edges as their vertices.

In general, the Voronoi polygon grid used to model the TIN will be used

to provide the spatial framework for a number of other object classes.

The only requirement that the implementation of TIN data will place on the

grid is that the density of the elevation points remains approximately an

order of magnitude above the density of the Voronoi polygon centers.

In this - and a number of other characteristics - a TIN object in a global

Voronoi grid parallels the combined characteristics of Hipparchus point

and line sets. This TIN will additionally consist simultaneously of two

levels of triangle/elevation data: high-volume triangles with source data

points as their vertices and low-volume, large triangles with cell-center

and end-points of cell edges as their vertices.

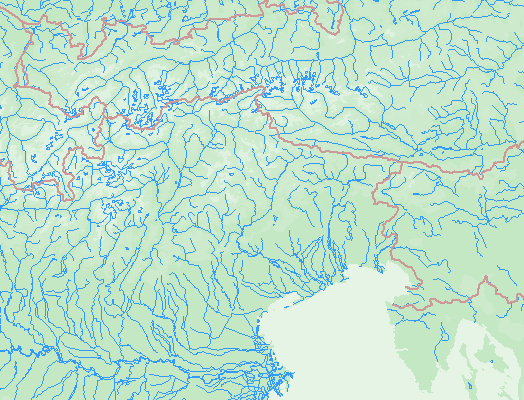

Figure 2: TIN in a Voronoi grid

The source data used in a construction of the Hipparchus TIN object

is a Hipparchus point set with elevations. The construction algorithm

proceeds cell by cell, transferring the point coordinate and elevation

data from the point set into a two-level TIN structure consisting of

both individual triangles and the values that describe the elevation

of cell-sector triangular vertices. In each cell, the process starts

with a selection of all those points that are inside the cell and those

points in the neighbor cells that fall within some distance of the

shared edge. A triangular grid produced in this step is then intersected

with the cell boundary. All triangle edge/cell edge intersection points

are assigned an interpolated elevation and marked as "points on the hull".

(This can be done, since the Voronoi polygon is at the same time a convex

hull of all points in its interior). These points are kept in the final

surface representation. Description of planar convex hull and algorithms

used to construct it can be found in Sedgwick (1983).

A second triangulation (that includes only cell interior and cell-edge

points) follows, this time as a faster, "forced hull" process.

The triangles of this second triangulation are stored - together

with the point coordinate and elevation data - in a final cell-oriented

series of structures representing the surface. Similar to other Hipparchus

objects, it is a hierarchical set of tables, at the center of which is

a table of "cell headers". It describes that part of the surface which is

"over" the cell, and its most important elements are:

- Cell identifier

- Coordinate array pointer and count

- Count of the cell interior points in the above

- Triangle array pointer and count

- Triangle neighbors array pointer and count

- Minimum, maximum and mean cell elevations

Figure 3: Different types of elevation points

The final TIN point array contains three types of points (clearly

distinguished in Figure 3), in order-of-magnitude decreasing numbers:

- Elevation points transferred from the source point set.

- Cell/triangle edge intersections with linearly interpolated elevations.

- Cell vertex points with spatially interpolated elevations.

Figure 4: Hypsographic rendering of a global TIN

The test data set (see Figure 4 for its hypsographic representation)

used to produce the illustrations of this paper, has been derived from a

5-minute gridded set of elevation points, and used extensively in the

development and code testing. A high density Voronoi grid was used as

a sampling framework, to avoid an artificially high

(and meaningless) data density in high latitudes, and to reduce

the point count to a level commensurate with the overall quality of

the elevation data. The result of this process was a Hipparchus point

set with about 200K points covering the planet in a generally uniform

pattern. In addition to its use in the testing, it is anticipated that

it will also be used to complete the planetary surface coverage for

local (regional, continental, etc.) elevation data sets available in

higher density and precision. This strategy is not unlike the frequent

use of a Hipparchus Voronoi index center-point set called "isotype",

which provides a similar function for regionally-biased grids.

The size of the disk files is approximately 2.5 MB for the source point

set, and approximately 8.4 MB as a TIN. In the current implementation,

all in-cell triangle indices are 32-bit integers; this removes any

practical restriction on the number of triangles in a single cell.

Elevations are recorded as 32-bit floating point numbers.

TIN Rendering

TIN rendering is implemented in a series of functions that belong to

the general section of the Hipparchus Library dealing with "geographics".

A TIN can be rendered in a "reduced dimensionality" mode, to generate

only the points and lines (triangle edges) without the full surface

representation. This mode was used to generate Figure 3. The Figure and

the other illustrations in this paper were created using a scripted

geographical workbench program called GALILEO, available for free download

from Geodyssey's web page at

http://www.geodyssey.com/.

TIN rendering is implemented in a series of functions that belong to

the general section of the Hipparchus Library dealing with "geographics".

A TIN can be rendered in a "reduced dimensionality" mode, to generate

only the points and lines (triangle edges) without the full surface

representation. This mode was used to generate Figure 3. The Figure and

the other illustrations in this paper were created using a scripted

geographical workbench program called GALILEO, available for free download

from Geodyssey's web page at

http://www.geodyssey.com/.

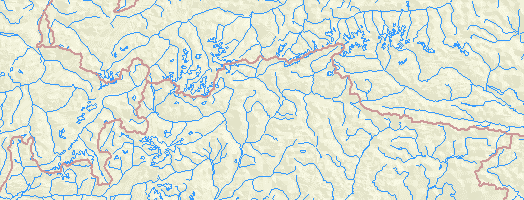

In cartographic applications a TIN is most often rendered as one of the two

graphical artifacts: a hypsographic scale color fill or a shaded surface.

The first assigns to each pixel a color dependent on the point elevation,

the second assigns a color dependent on the spatial orientation (slope and

azimuth) of the surface. Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the difference: both

show the map background-fill "layer" generated from a global TIN for an area of

the European Alps. Hydrographic network and political boundaries are also shown;

both are expected to be - to some extent at least - in an easily verifiable

relationship to the surface elevations.

Of the two, hypsographic scale color fill is more demanding of the graphical

programming, as it requires painting of pixels that belong to a single triangle

with a range of colors. (As opposed to shading, where all the pixels that

represent one triangle are in general of the same color). We will therefore

in the following concentrate on the hypsographic scale TIN rendering.

The central computation geometry process used in this type of rendering is the

ubiquitous triangle "gradient fill": given the x and y (image) coordinates of

three vertices and their associated "z" value, fill all pixels "inside" the

triangle with a color value commensurate to the interpolated value of "z".

This interpolated value is a value that a respective point of the plane

defined by three points (vertices) would have.

Figure: 5 Hypsographyc rendering

Figure: 6 Shaded rendering

Because of the multiplicity of environments in which this type of

rendering is performed, there are different levels at which the

division of labor between the application code (including any libraries

used), the graphical platform and - possibly - the display hardware

can take place. For the Hipparchus Library, we assumed there are at least

three such levels, and so provided the means to allocate control to a

lower level component (i.e., either the graphical platform or the

hardware) at any of those three levels. Their application program

interface can be described by the dimension, as follows:

- Point

- A single pixel is set to a color of the invoker's choice.

- Line

- Pixels of a scan-line segment with a given y and two end-point

x coordinates are set to a linear gradient of colors linearly

interpolated between given end-point color values.

- Area

- All pixels inside a triangle are filled with colors interpolated

between the given color values of the vertices.

The first level is available in even the most basic graphical application

development environments; the last one is implemented in most

"2-D accelerated" graphical device drivers and is supported in

graphical platforms targeting such devices. Thus an application rendering

a TIN would keep invoking Hipparchus Library functions to the

point-level under the Win32 API, and pass a whole triangle to an Open GL API.

Figure: 7 Sample surface, rendered in (relatively) large scale

A high-latitude section of the global TIN depicted in Figure 7

illustrates another unique advantage of the TIN representation in a

Voronoi grid. As mentioned before, all vertices on the cell edge will

have an interpolated elevation assigned to them. Likewise, a mean

elevation value for the whole cell is a natural by-product of the TIN

construction process. This data (cell mean and edges values) can be

used as a "generalized" representation of the same TIN: it consists

of a set of cell-segment level triangles, probably an order of magnitude

fewer per given area than the original TIN. (cf. outlined points and

large triangles formed by them in Figure 2). When the scale of rendering

becomes sufficiently small, the application can choose to render only

the large triangles, thus decreasing the rendering time considerably.

Applications will often store Hipparchus Binary Objects (on disk or in

a database) so that the low-volume cell-related values are separated

from the high-volume point coordinates. If this is the case, rendering

based only on the cell-level values (such as depicted on the small-scale

map in Figure 8) will require at least an order of magnitude fewer disk

transfers than the rendering of Figure 7 - despite the fact that both

are generated from the same surface object.

Figure 8: Cell-level generalization

Conclusion

A TIN as a Hipparchus Binary Object shares many architectural similarities

with point sets, line sets and regions constructed and recorded in the

context of global Voronoi grids. Its construction is based on a planar

triangulation within the cell boundaries. Triangle information storage

follows the common planar TIN model, but an additional set of elevations

is stored to represent the cell edge elevation profile. Simple,

straightforward and conjugate linear interpolation of elevations on the

edge guarantees that no artifact will be introduced at the cell edge.

The cell-based data structure representing the whole TIN provides a

simple and fast determination of the elevation at an arbitrary selected

surface point, and triangle rendering fits well with the API of common

graphical platforms. A novel approach to the problem of generalized

rendering is another benefit of the Voronoi grid.

References

-

Ambroziak, R.A., Cook C.A., Woodwell, G.R. and Wicks R.E.:

Data, Software, and Applications for Education and Research in Geology

(CD publication), United States Geological Survey Open File Report 93-231, 1993.

-

Bomford, G. Geodesy, London, Oxford University Press, 1975 ed.

-

Dutton, G. H.:A Hierarchical Coordinate System for Geoprocessing and Cartography,

Springer Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 1999.

-

Lischinski, D.:Incremental Delauny Triangulation, article published in

The Graphics Gems Series, Volume IV, pp. 47-59, AP Professional 1994.

-

O'Rourke, R.:Computational Geometry in C, Cambridge University Press 1994.

-

Sedgewick, R.:Algorithms, Addison-Wesley 1983.

...

|