Hipparchus Geopositioning Model: an Overview

Hrvoje Lukatela,

Geodyssey Limited

http://www.geodyssey.com/

Paper presented at AUTO-CARTO 8, Baltimore, March 1987

Document URL: http://www.geodyssey.com/papers/hlauto8.html

Abstract

This paper introduces a novel digital geopositioning model. It is

based on computational geodesy in which direction cosines are used

instead of the conventional -angular- ellipsoid normal representation,

and eccentricity term expansions are replaced by iterative algorithms.

The surface is partitioned by a spheroid equivalent of the Voronoi

polygon network. The model affords seamless global coverage, easily

attainable millimetric resolution, and data-density sensitive location

indexing. Numerical representation of 0, 1 and 2 dimensional objects

is in complete accordance with the unbounded, spheroidal nature of

the data domain, free from any size, shape or location restriction.

Efficient union and intersection evaluations extend the utility of the

relational technique into the realm of geometronical systems with

non-trivial spatial precision requirements. Digital modelling of orbital

dynamics follows closely the numerical methodology used by terrestrial

geometry. The Hipparchus software package includes the

transformations and utility functions required for efficient generation

of transient graphics, and for the communication with systems based on

conventional cartographic projections.

Introduction

A numerical geopositioning model is an essential element of any system

wherein a dimension of space enters into the semantics of the

application - and therefore into the software technique repertoire - in a

fundamental way. It consists of location attribute data definitions

and computational algorithms, which allow position sensitive storage

and retrieval of data, and provide a basis for evaluation of spatial

relationships. (The term "spatial relationship" is used in this paper

to describe the formal statement of any practical spatial problem

which deals with positions of real or abstract objects on - or close

to - the Earth surface. Their nature can vary; examples might include

geodetic position computations, course optimization for navigation in

ice-infested waters or determination of the most probable location of

objects remotely sensed from a platform in the near Space.)

If the location attributes of data elements in a computer system are

used exclusively for the generation of a small-scale analog map

document, the demands made of a geopositioning model are few and

simple. When the area of coverage is limited, and projection

geometry, spatial resolution and partitioning of the data can be made

directly compatible with same characteristics of all future required

products, a single plane coordinate system is often employed. Such a

system is usually based on one of the large-area conformal projections

(e.g. Lambert, Gauss-Krueger, etc.), and provides adequate means to

identify positions, partition the data, and construct a location

index. The model may even allow limited spatial analysis.

However, with the increase of the area of coverage and the functional

power of information systems, the nature of the problem changes

considerably.

Precision requirements usually exceed the level of difference between

planar coordinate relationships and the actual object-space geometry.

In most cases, the generation of an analog map is reduced to a

secondary objective. Location attributes are primarily used to

support the evaluation of spatial relationships required by the

application. Indeed, as the volatility and volume of data grows, it

becomes increasingly common that a location-specific item enters a

system, contributes to the evaluation of a large number of spatial

relationships, and is ultimately discarded, without ever being

presented in the graphical form.

Even in systems used primarily to automate the production of analog

documents, there is often a need to accommodate many different

projection, resolution and data partitioning schemes on a continental

or even global scale.

A point is thus quickly reached where geopositioning model must

satisfy very demanding functional requirements, yet any restriction on

the data domain becomes unacceptable. From the application point of

view, the mapping from an atomic surface fraction into a distinct

internal numerical location descriptor must be global, continuous and

conjugate.

Faced with these requirements, manual spatial data processing resorts

to a combination of two techniques. A set of multiple planar

projection systems (e.g. UTM "zones") is used to achieve - seldom

successfully - the global coverage. Initially simple calculations are

cluttered with various "correction" terms in order to deal with

differences between planar coordinates and true object geometry.

A failure to understand the precise nature of spatial data

(especially, by ignoring the profound conceptual difference between an

analog map and the true data domain) often leads to a blind transplant

of conventional cartographic techniques into a computerized system.

This seldom results in a satisfactory geopositioning model:

cartographic projections are notorious for their computational

inefficiency; global coverage usually requires the use of

location-specific transformations. Programming becomes progressively

more complex as the precision requirements increase. Boundary

problems are difficult to solve; this imposes discontinuities or size

restrictions for the models of spatial data objects. Finally,

classical cartography offers little or no help in modelling of the

near-space geometry. The same system can therefore be forced to

employ two disparate numerical methodologies: one for the positions

on the Earth surface and quite another for orbital data. This

presents an increasingly serious problem in many emerging high

data-volume applications.

Design (or selection) criteria for a generalized location referencing

numerical model and software will change from one computerized

information system to another, but will be based - usually - on the

size of the area of interest, spatial resolution, anticipated data

volume, optimal computational efficiency, logical and geometrical

complexity of objects modelled, and on the level of precision with

which all these elements can be defined before the system is built.

Nevertheless, it is possible to list important functional requirements

that will pertain to a majority of extended coverage geographic

information systems:

-

Unrestricted numerical representation of arbitrarily-sized

and -shaped objects with 0, 1 and 2 dimensions (i.e. points,

lines, regions) relative to the surface of the Earth, and

efficient evaluation their unions and intersections.

-

Global coverage, without any regions of numerical instability

or deterioration; ability to precisely model spatial

relationships resulting from the unbounded, spheroidal nature

of the data domain.

-

Variable (application controlled!) levels of positional

resolution and computational geometry precision; up to

sub-millimeter level for location framework or field-measurement

related data.

-

High utilization level of the coordinate data-storage space.

-

Construction of data density and system activity level

sensitive surface partitioning and indexing scheme; capability

of dynamic re-partitioning in order to respond to a change in

density or activity pattern of an operational system.

-

Ability to effectively model the time/space relationships of

surface, aeronautical and orbital movements.

The quality of a generalized geopositioning model will obviously

depend not only on the extent to which the above criteria have been

satisfied, but on its software engineering potential as well. The

model must be capable of being implemented in program code which is

efficient, reliable, portable, and easily interfaceble to a large

number of different types of data-access services (i.e. file and

indexing schemes, database software packages e.t.c.) and application

problem-solving programs.

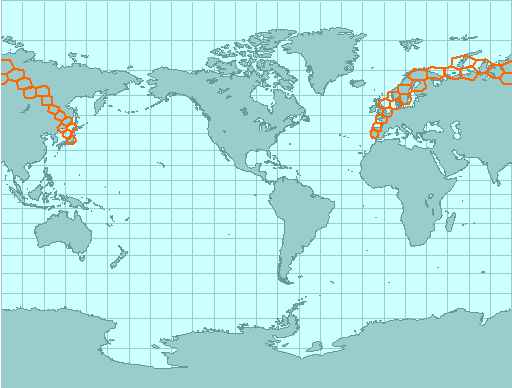

Fig. 1: Hipparchus ellipsoid surface partitioning scheme

Fig. 1: Hipparchus ellipsoid surface partitioning scheme

The geopositioning model presented here consists of three key

components: a) spheroidal cell structure analogous to planar Voronoi

polygons; b) computational geodesy based on closed iterative

algorithms, and c) an unlabored representation of global ellipsoid

coordinates in terms of a cell identifier and description of location

within the cell. Since the computational bridge between the global

position and the location within the cell consists of a pseudo-

stereographic ellipsoid-plane transformation, Hipparchus has been

chosen as the name for the model. (Hipparchus, (180-125 B.C.) -

inventor of stereographic projection: the first truly practical

geopositioning model.)

The Hipparchus model provides a unique spatial framework,

and includes the algorithms necessary to encode data and evaluate spatial

relationships. In doing so, it attempts to satisfy - to the highest

extent possible - all the requirements mentioned above. The nature of

the framework and principles of its data manipulation techniques will

be examined next in some detail.

Global Ellipsoid Coordinates

A plane or sphere can be used to represent the surface of the Earth

only for limited-area, low-precision computations. A general purpose

geopositioning model will, however, require a better fitting surface.

Typically, a quadric, biaxial (rotational) ellipsoid is employed.

(Triaxial ellipsoid and various sets of polynomial correction terms to

a biaxial ellipsoid have both been employed in geodetic calculations

and proposed for general cartographic use. The discussion of

potential merits of those surfaces, and the ability of the proposed

model to accommodate them numerically, are beyond the scope of this

text.) The parameters of size and eccentricity of the reference

ellipsoid can be determined by a combination of theoretical

investigation into the equilibrium shape of a rotating near-liquid

body and terrestrial geometry and satellite orbit observations. This

is an open-ended process, resulting in occasional corrections of

ever-decreasing magnitude.

The position on the surface of the ellipsoid can be represented

numerically in many different ways. Conceptual clarity of the model,

as well as practical software engineering considerations, demand that

one such representation be used as a canonical form of global location

descriptor throughout the model. The selection of this numerical form

is one of the most critical decisions in the design of a

geopositioning model.

The traditional angular measurements of latitude and longitude are

extremely unsuitable for automated computations. Few, if any, spatial

problems can avoid multiple evaluations of trigonometric functions.

Moreover, convoluted programming techniques are often necessary to

detect areas of numerical instability and adjust an algorithm

accordingly. It would be simple to use Cartesian point coordinates

instead, but the domain would no longer be restricted to the ellipsoid

surface. An additional condition would have to be incorporated into

the statement of most surface-related geometry problems.

The geometrical entity described by latitude and longitude is a vector

normal to the surface of ellipsoid in the location thus defined. This

vector can be expressed by its direction cosines, and a normalized

triplet can be used as coordinates of a surface point. This appears

to be an ideal canonical location descriptor: the domain is restricted

to the surface; numerical manipulations based on vector algebra

productions are easy to program and simple to test, and a common

64-bit floating point numbers will yield sub-millimeter resolution

even at radial distances that are an order of magnitude above the

surface of the Earth.

Conventional formulae for the solution of ellipsoid geometry problems

were typically obtained by expansion in terms of an ascending power

series of eccentricity. While this was unavoidable for problems

lacking a closed solution, it was also often used in order to reduce

the number of digits which had to be carried in a numerical treatment

of a geodetic problem with a limited spatial extent. As long as the

eccentricity of the reference surface was constant, any a priori

precision criterion could be satisfied by either finding the maximum

value of the remainder dropped, or - more commonly - by deciding on

the threshold exponent beyond which terms could be ignored for a whole

class of practical problems.

Formulae thus obtained are useful for manual calculations but do not

provide a sound base for the construction of efficient and

data-independent computer algorithms.

The insight required to decide whether or not a particular set of

formulae can or can not be used to solve a given problem is difficult

to replicate in a program. Expansions must be checked and programmed

with extreme care, since the influence of errors in higher terms can

be easily mistaken for unavoidable numerical noise in the system.

While the assumption of moderate and constant elliptical eccentricity

might be valid for terrestrial problems, it represents an undue

limitation in systems incorporating orbital geometry. Finally, in

most computer hardware environments the full number of significant

digits required to achieve sub-millimeter resolution can be used

without any penalty in the execution time.

With the appropriate statement of conditions, all ellipsoid geometry

problems of single periodic nature (i.e. those whose differential

geometry statement does not lead to elliptic integrals) can be solved

very efficiently, to any desired level of precision, using an

iteration technique based on the alternate evaluation of conditions

near the surface and at the point where the normal is closest to the

coordinate origin. Ellipsoid coordinates consisting of three

direction cosines offer significant advantages in all numerical

algorithms required to carry out this iteration. The distinct

advantage of this method (compared to a program based on expansion

formulae) lies in its automatic self-adjustment to the computational

load. The number of iterations will depend on the precision

criterion, physical size of the problem and the measure of ellipsoid

(or ellipse!) eccentricity. The same program can therefore be used

for all global geometry problems of a given type, with full confidence

that the desired precision has been achieved - in each individual

invocation - through a minimum number of arithmetical operations

necessary.

This approach can be applied not only to conventional geodetic

problems but also to solve problems dealing with both surface and

spatial entities. In particular, it will be effective solving the

problems which deal simultaneously with the ellipsoid surface and with

orbital parameters which are themselves of quadric nature.

It should be noted that only the framework data must be permanently

retained in global ellipsoid coordinate values. As explained below,

volume data coordinates can be stored in a much more efficient format,

and transformed into ellipsoid coordinates in transient mode, whenever

these are required.

Surface Partitioning And Location Indexing

One of the essential facilities required for the design and

construction of a geographical database is a surface partitioning

scheme. On the simplest level, this provides a basis for indexing and

retrieval of location-specific data. Even more important will be its

use for efficient run-time evaluation of spatial unions and

intersections, probably the most critical facility in construction of

a fully relational spatial database system.

Where the potential for extended coverage is required, the

partitioning scheme must be capable of dealing with the complete

ellipsoidal surface. This can not be achieved using any of the

regular tessellations which have been proposed as the base for

hierarchical data-cells: beyond the equivalent of the five Platonic

solids, the sphere can not be divided into a finite number of equal,

regular surface elements.

Various schemes based on latitude/longitude "rectangles" are often

used for large coverage or global databases. However, resulting cell

network is hard to modify in size and density, high-latitude coverage

can be restricted or inefficient, and in most cases the approach

forces the use of unwieldy angular coordinates.

By contrast, the partitioning scheme used in the Hipparchus model

is based on spheroidal cells analogous to planar Voronoi polygons.

The definition of the structure is simple. Given a set of distinct

(center)points, a spheroidal polygon-cell corresponding to one of them

is defined as a set of all surface points "closer" to it than to any

other member of the centerpoint set. For each surface point, the

minimum "distance" to any point in the set of centers can be

determined: if there is only one centerpoint at such a distance, the

point is within a cell. If there are two, it belongs to an edge. If

there are three, the point is a vertex. A dual of the set of polygons

is obtained by connecting the centerpoints which share an edge.

The application can define a pattern of cells by any purposefully

distributed set of centerpoints. Since these are defined by their

normals, the partitioning scheme is completely free from condescending

to any numerically singular surface point. The distribution of

centerpoints can be based on any combination of criteria selected by

the application: data volume distribution, system activity patterns,

maximum or minimum cell size limits. It can even represent an existing

set of spatial framework items, e.g. geodetic control stations.

A sort-like algorithm produces the digital model of the dual. The

cell frame structure is thus reduced to a list of global, ellipsoid

coordinates of centerpoints and a circular list of neighbor

identifiers for each cell. If the application requires that a limit

be placed on the maximum "distance" between neighboring centerpoints,

the algorithm must be capable of bridging the "voids", and null items

must be recognizable in the circular list. This data structure is

used extensively by all spatial algorithms. Unlike systems in which

location of the cell is implied in its identifier, the Hipparchus

model requires explicit recording of the global coordinates of cell

centers. Method of storage and access to this data can therefore have

considerable influence on the efficiency of spatial processing.

A cell is assigned an internal coordinate system with the origin at

its centerpoint. As mentioned before, the mapping function between

global and cell systems is an ellipsoid-modified stereographic

projection. The "transformation algorithms" (in both directions)

consist therefore of nothing but a few floating-point multiplications.

"Finite Element Cartography". If a large volume of data has to be

transformed into output device coordinates based on a specific

conventional cartographic projection, only a few points on the cell

(or the display surface) frame will have to be transformed using a

rigorous cartographic projection calculation. Based on the frame

data/display correspondence, parameters of a simple polynomial

transformation are easily calculated. Volume transformations will

again require only a few multiplications, and can be set to produce

the result directly in hardware coordinates of an output device. This

type of manipulation can be of particular value if a complex

geometronical function has to be applied over the complete surface of

a dense data set, for instance in transient cartographic restitution

of digital remote sensor image material.

One of the most often executed algorithms in the model will probably

be the search for the "home cell" of an arbitrary global location.

Selection of the first candidate cell is left to the application, in

order to exploit any systematic bias in either transient or permanent

location reference distribution. A list of all neighbors is

traversed, and distances from the given location to the neighbor

centerpoints are determined. If all these distances are greater than

the distance from the current candidate centerpoint, the problem is

solved. Otherwise, the minimum value indicates a better candidate.

While the algorithm is very straightforward, its efficiency will be

extremely sensitive to the selection of the spheroid "distance"

definition and numerical characteristics of global coordinates. The

same will apply to most combined list-processing and numerical

algorithms employed by the model.

Fig. 2: Trace of home cell search algorithm

Fig. 2: Trace of home cell search algorithm

While Voronoi polygons have often been used in computer algorithms

solving various classes of planar navigation problems, at the time of

this writing no record was found of the use of an equivalent global,

spheroidal structure as a partitioning scheme in a geometronical

computer system.

Modelling Of Spatial Data Objects

Points: Digital representation of a point data element is simple:

it consists of a cell identifier and local (cell) coordinates. Even with

fairly large cells, the global-to-local scaling will ensure equivalent

spatial resolution in case where local coordinate values have only

one-half of the significant digits used for global coordinate values.

Since the efficiency of external storage use and the associated speed

of I/O transfer can be of extreme importance in a large database, the

following numerical data are of interest:

If a 64-bit global, a 32-bit local coordinate values and 16-bit cell

identifier are used, the volume data point representation will require

only 80 bits, and will still yield sub-millimeter resolution.

80 binary digits are capable of storing 2**80 (approximately 1.2E24)

distinct values; the surface of the Earth is approximately 5.1E20

square millimeters. The ratio of these two numbers (approximately 69

out of 80) represents the theoretical memory utilization factor;

practically, the margin allows significant variation in cell size and

use of various computational conveniences (floating point notation,

cell range encoding, e.t.c.). This utilization factor compares to 69

bits out of 128 if the point is represented by latitude/longitude in

radian measure, and 69 out of 144 bits (typically) if a conventional,

wide-coverage cartographic projection system plane identifier and

coordinates are used. Furthermore, various external storage

compression schemes that take advantage of the re-occurring cell

identifier are likely to be significantly simpler and more effective

than any compression scheme of a pure numerical coordinate value.

It is important to note that in Hipparchus model cell coordinates

of a point are not used for a numerical solution of metric problems; their

purpose is to provide a compressed coordinate storage format for

high-volume data, and to facilitate generation of the transient,

analog view of the data.

Lines: One-dimensional objects are represented by an ordered

list of cells traversed by the line, and - within each cell - a list,

(possibly null) of vertices in the point format described above. If

the application requires frequent evaluations of spatial unions and

intersections, it might be efficient to find and store permanently all

points where lines cross cell boundaries. Their internal

representation (permanent or transient) is somewhat modified in order

to restrict their domain to the one-dimensional edge, but their

resolution and storage requirements will be comparable to the general

point format used by the model.

Regions: Two-dimensional objects are represented by a directed

circular boundary line and an encoded aggregate list of cells that are

completely within the region. When compared to simple boundary line

circular vertex list, this structure makes the evaluation of spatial

relationships significantly more efficient. The solution will often

be reached by simple manipulation of cell identifier lists, instead of

the evaluation of boundary geometry. The number of cases where,

ceteris paribus, this will be possible, will be inversely proportional

to the average cell size. (In example in Fig. 3, boundary geometry

examination will be confined to three cells.) This representation of

a two-dimensional object is a combination of the traditional boundary

representation and schemes based on regular planar tessellations. It

offers the high resolution and precision usually associated with the

former, while approaching the efficiency of relational evaluations of

the latter. In addition, it does not violate the true spherical nature

of the data domain. For instance, if [A] is a region, then NOT [A] is

an infinite, numerically ill-defined region in a plane. By contrast,

on any spheroidal surface NOT [A] is the simple finite complement.

Fig. 3: Intersection of two-dimensional objects

Fig. 3: Intersection of two-dimensional objects

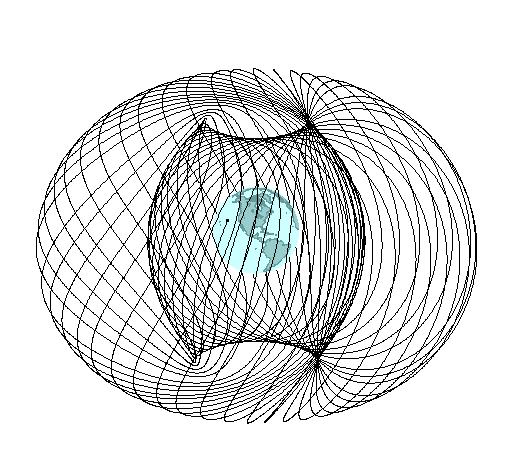

Orbit Dynamics: Practice abounds with examples of problems

encountered in attempts to integrate remote sensing and existing terrestrial

data. Even in instances where the spatial geometry can be defined with

sufficient precision, it is common to cast (by "pre-processing") the

digital image produced by a satellite sensor into a specific plane

projection system and pixel aspect ratio and orientation. This

unnecessarily increases the entropy of remotely sensed data available

to applications requiring different or no planar castings. In many

instances, problems will disappear if the application is given the

ability to manipulate the original, undistorted, observation geometry.

A general-purpose geopositioning software tool must therefore provide

efficient evaluation of basic time/geometry relationships within the

orbital plane, and the ability to transfer the locations from an

instantaneous orbit plane to its primary frame of spatial reference.

(More complex calculations are probably application-specific and are

restricted to infrequent adjustments of orbit parameters.)

The geometry functions described already suffice to define any orbit

at the convenient epoch - e.g. the time of the last parameter

adjustment. To find a position (in the orbital plane) of a platform

at a given time, a direct solution of the problem postulated by

Kepler's second law is required. (Same as in geodetic problems

mentioned previously, this "direct" problem requires an iteration,

while the "inverse" yields a closed solution.) Any increase of orbit

eccentricity will affect the number of iterations, but the same

software component can be used to solve both near-circular and steep

orbits. Common 64-bit floating point representation will preserve

millimetric resolution even for geosynchronous orbits. Rigorous

modelling of general precession can be achieved simply by an

additional vector rotation about the polar axis. This is combined

easily with sidereal rotation, required in any case for transfer of

position between the inertial and terrestrial frames of reference.

Fig. 4: Orthographic view of a precessing orbit

Conclusion

Use of computers in mapping is as old as the computer itself: the

first commercially marketed computer, UNIVAC 1, was used in 1952 to

calculate Gauss-Krueger projection tables. With the development of

computer graphics, it quickly became common to store and update a

graphical scheme representing a map. Until very recently, the main

object of this process remained the production of graphical output

that was not substantially different from a conventional analog map.

While the production of the map was thus computerized, the ability of

an "end-use" quantitative discipline to employ a computer to solve

complex spatial problems was not addressed. The use of a "computer

map" was precisely the same as that of a traditional, manually

produced document.

All quantitative disciplines are facing the same demands as

cartography to increase precision, volume and complexity of data which

can be efficiently processed. Hence, computer applications in those

disciplines require "maps" from which spatial inferences can be

derived not only by the traditional map user, but also by a set of

computer application programs. To a limited extent only, this has

been achieved in applications which could tolerate severe limitations

on area of coverage, data volumes, or spatial resolution requirements.

Location attributes in these computer systems are usually based on an

extended coverage ellipsoid-to-plane conformal projection: a numerical

model developed for a completely different purpose.

Computer systems requiring extensive spatial modelling combined with

high resolution and global coverage need powerful yet efficient

numerical georeferencing models. It is unlikely that these can be

based on conventional cartographic techniques. Numerical methodologies

designed specifically for the computerized handling of spatial data

have the best potential for providing generalized solutions.

...

|