Ellipsoidal Area Computations of Large Terrestrial Objects

Hrvoje Lukatela,

Geodyssey Limited

http://www.geodyssey.com/

Paper presented at the International Conference on Discrete Global Grids,

Santa Barbara, 26 - 28 March 2000

Abstract

The mathematics of area computation on the ellipsoidal planetary

surface is straightforward; it is however rarely implemented in

its rigorous form. Most spatial information systems dealing with

two dimensional objects treat the area not as a simple derivative

of the object definition geometry, but rather as an artifact of

its representation in a particular planar representation. This

approach fails when no single, canonical planar representation is

either practical or desirable, or when the spatial extent of the

object exceeds the useful coverage of a single planar projection.

The Hipparchus geopositioning model represents two dimensional

terrestrial objects in the context of an irregular global grid

consisting of spheroidal Voronoi polygons. This paper presents

the strategy and outlines the implementation of area computation

for such objects. It assumes that efficiency is as important as

is the precision, and that the objects can be of any size, shape

and topological complexity. The speed and accuracy of the

computation is examined by applying it to a large, global object

of high data volume and considerable topological complexity.

Introduction

This paper presents a particular numerical solution to a rather

straightforward and well-defined mathematical problem: given a

two-dimensional object of an arbitrary complex topology on a surface

of an ellipsoid of rotation, find its area. Several elements of the

underlining mathematics are worth noting at the outset:

This paper presents a particular numerical solution to a rather

straightforward and well-defined mathematical problem: given a

two-dimensional object of an arbitrary complex topology on a surface

of an ellipsoid of rotation, find its area. Several elements of the

underlining mathematics are worth noting at the outset:

-

The total surface of an ellipsoid of rotation can be expressed as

a closed (but transcendental) function of its semi-minor and

semi-major axes.

-

The area of a pseudo-trapezoidal figure bounded by two meridians

and two parallels leads to a single ellipsoidal integral over the

latitude domain.

-

The area of a triangle - with geodesics as its sides - leads to

a double ellipsoidal integral over the geodesic lengths.

Even the mathematically simpler - trapezoidal - decomposition

results in an integral that requires a binomial series expansion.

In addition, the substitution of the continuously changing width of

latitude-bands for a figure bounded by a geodesic leads to an

approximation, the magnitude of which depends on both the band height

and the local azimuth of the geodesic. The decomposition into triangles

results in a similar, but even more complicated numerical solution.

In either case, the decomposition of topologically "deep" two

dimensional objects into either pseudo-trapezoidal or triangular

components can lead to rather complex implementation problems.

A good overview of the ellipsoidal geometry and the algebra

and calculus used to implement common geodetic computations can

be found in either Jordan (1958) or Bomford (1975).

Figure 1: A two-dimensional object in a spheroidal Voronoi grid

If the two-dimensional ellipsoidal surface object is already

represented in a form which provides a convenient basis for the

geometrical decomposition, it will be advantageous to use such

representation as a basis for the area computation. This is the

case in the Hipparchus Geopositioning Model, where an object is

represented in an irregular global grid of Voronoi polygons.

(The full presentation of this model is outlined in a web-resident

publication titled:

Hipparchus Geopositioning Model: an Overview). It is an

example of a "constructive index", where the object geometrical

integrity remains intact, and the infrastructure required to

access parts of the object that belong to one index block

(data cell, tile... etc.) exists "in addition" to the data

defining its geometry. Figure 1 depicts an object in a global

Voronoi grid. We will - later on in this text - recapitulate

those features of this type of object representation which

influence directly the area computation. For now, we note only

that there are some cells ("boundary cells") through which the

object boundary "meanders" and some cells ("interior cells")

which are completely encompassed by the object. The area of an

object will be determined by summing up the area of all interior

cells and adding to this the partial area - that portion covered

by the object - of all of its boundary cells.

Area of Ellipsoidal Voronoi Cells

We will first outline the method for determining the area of any

Voronoi cell. This is done by subdividing the cell into triangles

with neighbor edges as a base and cell center as the opposite

vertex. The edges of these triangles are segments of great

circles on a sphere related to the ellipsoid (on which both the

object boundary and cell-center coordinates are defined by their

geodetic coordinates) by conformal ellipsoid to sphere mapping.

While these edges are not ellipsoidal geodesics, the maximum line

displacement is both relatively small (2.5 meters for a line similar

to the one discussed below in the context of UTM mapping) and the

"gain" and "loss" tend to be of the same magnitude when all the edges

along the cell boundary are considered. The area of these triangles

is then computed by spherical productions, but using a constantly

changing radius determined by the mean curvature of the ellipsoid

surface in the cell center.

We will first outline the method for determining the area of any

Voronoi cell. This is done by subdividing the cell into triangles

with neighbor edges as a base and cell center as the opposite

vertex. The edges of these triangles are segments of great

circles on a sphere related to the ellipsoid (on which both the

object boundary and cell-center coordinates are defined by their

geodetic coordinates) by conformal ellipsoid to sphere mapping.

While these edges are not ellipsoidal geodesics, the maximum line

displacement is both relatively small (2.5 meters for a line similar

to the one discussed below in the context of UTM mapping) and the

"gain" and "loss" tend to be of the same magnitude when all the edges

along the cell boundary are considered. The area of these triangles

is then computed by spherical productions, but using a constantly

changing radius determined by the mean curvature of the ellipsoid

surface in the cell center.

The method presented here shares two salient principles with the one

devised by Tobler and Kimerling, as described in Kimerling (1984):

the first is the use of local ellipsoidal radii in spherical triangle

area productions and the second is the tracking of positive and

negative area contributions based on the direction of the boundary

segment. The latter parallels the procedural makeup of the planar

polygon area computation and provides an effective way to keep the

non-numerical programming complication within reason, while at the

same time avoiding any restriction on the level of the topological

complexity of the objects for which the area is calculated.

In geodetic computations, the expression for the mean radius of

the ellipsoid surface in a given point is commonly referred to as

Gauss' formula: r = sqrt(m*n)

(where m and n are radii of the meridian

and prime vertical, respectively). The conventional computation of

the mean radius uses the ellipsoidal eccentricity term - an

unnecessary complication in computation on digital computers.

The preferred method uses tsq: a latitude

(phi) dependent square of the free term of the tangential

plane, defined directly as a function of the sine and cosine of the

point of tangency and the major and minor ellipsoid semi-axes

(a and b respectively), as follows:

s = sin(phi)

c = cos(phi)

tsq = a*a*c*c + b*b*s*s

r = (a*a*b)/tsq

This method of mean ellipsoid radius computation is especially

convenient for systems such as Hipparchus, which represent the

location of a point using the direction cosines of its ellipsoid

normal: the evaluations of s and c require

no expensive transcendental computations. Also, the tsq term finds a

repeated use in many different ellipsoid geometry propositions.

No a priori error term has been derived for this "finite element"

ellipsoid-to-sphere approximation; the total area of all cells so

computed can however be compared (and adjusted) to the total

ellipsoid surface. (See below, under "Some Numerical Results",

for details). Since we assume that a system will be required to

produce the area of many different objects, represented in the

context of the same global grid, an array of areas - one element

for each cell - will be conveniently stored with the

other data in the structures representing the Voronoi polygons.

Computing the area of a spherical triangle for which the lengths of

all three sides (a, b and c) are given can be

done using two different approaches: by applying Legendre's

approximation, or by L'Huilere's theorem. The former states that

the area of a spherical triangle will be getting closer to the area

of a planar triangle with the same side lengths, as the ratio of the

triangle perimeter divided by the spherical radius gets smaller.

The latter is, on the other hand, a rigorous evaluation of the

spherical triangle area in terms of the three sides. To compare the two:

P = sqrt(s*(s-a)*(s-b)*(s-c))

versus:

P = 4*atan(sqrt(tan(s/2)*tan((s-a)/2)*tan((s-b)/2)*tan((s-c)/2)))

(where s is the common shorthand notation for the

half-sum of all three sides)

Implementations which impose a low maximum cell radius limit might

take advantage of a considerably faster Legendre's approximation.

The implementation used to derive the numerical examples given below

is, however, based on the second (L'Huilere's) expression, applied to a

"local" sphere with the radius equal to the mean ellipsoid radius at

the cell center.

Area Computation in Boundary Cells

The determination of the area of an object in a boundary cell

requires no additional mathematics. If an object is topologically

well-defined, its area inside a boundary cell will consist of a

finite number of distinct "faces", each bounded by a closed ring.

The ring may consist of either the segments that all belong to

the object boundary, or, in the general case, a combination of object

boundary and cell edge segments. In a procedure directly

paralleling the usual implementation of planar polygon area

computation, we can traverse the ring, and accumulate triangular

areas subtended from each segment and the coordinate origin -

adding or subtracting, depending on the radial direction of

the boundary segment respective to the coordinate origin.

The determination of the area of an object in a boundary cell

requires no additional mathematics. If an object is topologically

well-defined, its area inside a boundary cell will consist of a

finite number of distinct "faces", each bounded by a closed ring.

The ring may consist of either the segments that all belong to

the object boundary, or, in the general case, a combination of object

boundary and cell edge segments. In a procedure directly

paralleling the usual implementation of planar polygon area

computation, we can traverse the ring, and accumulate triangular

areas subtended from each segment and the coordinate origin -

adding or subtracting, depending on the radial direction of

the boundary segment respective to the coordinate origin.

Figure 2: Geometry of a boundary cell

We will next identify some area computation pertinent features

of the object geometry definition in an example of a boundary cell,

as depicted in Figure 2. (It is an enlarged part of the object shown

in Figure 1). The topological decomposition of the object presented

in the following is essentially the same as it would be if the

object was a planar one - thus additional details, definitions and

code segments can be found in many sources describing planar

computational geometry - for instance Bowyer (1983).

The fundamental geometrical element is a "fragment":

an ordered array of vertices forming the object boundary, in

either a closed ring, or starting and ending on the cell boundary.

There are four boundary fragments in the example: a, b,

c and d; two of them are closed rings (a and

b), and two are connecting cell boundary crossing points

(fragment c, connecting crossing points 1 and 2;

and fragment d, connecting points 3 and 4).

For each fragment, we note that the start point is the point where

the object boundary "enters" the cell, and the fragment end point is

the point where the boundary "exits" the cell.

Fragments are directed in the mathematically positive sense, such that

the object interior is always on the left-hand side of the boundary

line. This ensures that the "voids" will produce a negative

contribution to the total area, regardless of how "deeply nested"

the topology of the object is.

One or more fragments form the boundary of a "face" - a single

continuous, connected area. In the example, there are three faces:

A, B and C. Faces A and B are

formed by single ring fragments a and b. Face C

is formed by fragments c and d. In addition to the two

fragments, the boundary of face C also requires two cell-edge

line segments: first one from the end point of the fragment d,

to the cell vertex s, to the start point of the fragment

c and the second, from the end point of fragment c,

through the cell vertices u, p, q and r,

to the start point of the fragment d.

A canonical representation of the Hipparchus system two-dimensional

objects identifies only the distinct boundary fragments, and not

the faces they form. No spatial algebra proposition

(e.g., "polygon overlay") requires this knowledge, and all such

propositions would thus be burdened with the additional code if

required to keep track of the fragment/face relationship.

The area computation algorithm must therefore "construct" the

faces as and when required. This information is used implicitly,

in the ring traverse order, and is not stored permanently.

This "construction" is trivial for faces which are formed by a

single closed fragment (A, B); and somewhat involved

for the faces (C) that are composed of both object and cell

boundary.

The computation of an object area in a boundary cell consists of

two phases. The first one is a simple traverse of all fragments.

Closed fragments present no special problem: their area

contribution is accumulated as they are encountered.

For open fragments (i.e., those that start and end on the cell

boundary) both boundary crossing points are stored in a table,

which lists the point type (start or end), fragment identification

(in form of a pointer), cell neighbor index of the crossing

point, and the distance from the closest "upstream" cell vertex.

If the cell across the p-q edge is the first

(index 0) neighbor in the (circular) list of cell neighbor

cells, then for fragment c two entries are stored in the

table: one for entry point 1, with neighbor index 3

and s-1 distance; and another for exit point 2,

with neighbor index 4 and t-2 distance.

Similar entries would be made for boundary points 3 and

4, when fragment d is processed. In addition, a list

of fragments is doubly-linked with the table elements. This ensures

that at the end of the traverse of an open fragment, its end-point

can be retrieved from the table.

The boundary crossing point table is then sorted, with the neighbor

index as the primary and upstream vertex distance as the secondary

ordering element. The table in the example would thus be reordered

as 3, 4, 1, 2. This table is considered

to be circular, just like the ordered list of cell neighbors.

In the second phase we traverse the faces by starting at the first

previously unvisited cell entry (fragment start) point retrieved

from the sorted table. The table element is marked as "visited",

and the fragment is followed - accumulating the area at each fragment

vertex - until the fragment end (cell exit) point is encountered.

The table is then searched for the next (in the circular sorted

table order) fragment start point. When one is found, the cell

vertices (if any) between the two points are traversed and their

area contribution is accumulated. If the found entry point has not

been visited before, we mark it and traverse its fragment, if it was

visited before we have completely encircled a face. Another

"unvisited" entry point from the table (if any are left) starts

the same process for the next face; if none are left, the boundary

cell area computation is completed.

Some Numerical Results

The numerical testing and verification of the area computation

presented here differs markedly from that used in Kimerling (1984).

There, the comparison is made between the area of a rhomboid

computed from its vertex coordinates in UTM projection and the

area computed on the ellipsoid using geodetic coordinates of the

four equivalent vertices. However, the straight line in UTM projection

with a length of almost 250 km (for the largest of the verification

figures) is in the general case different from the projection of the

geodesic - in this case, the maximum displacement between the two

is considerable, and varies significantly between the easterly

(11.3 meters) and westerly (28.9 meters) edges. If the geodesic

edges connecting the vertices on the ellipsoid are projected

back to the UTM plane (as a sufficiently dense array of vertices),

and the area is recomputed, it changes by approximately 1 in 10000 -

quite a bit above the precision level of the ellipsoidal area

computation claimed by both methods.

The numerical testing and verification of the area computation

presented here differs markedly from that used in Kimerling (1984).

There, the comparison is made between the area of a rhomboid

computed from its vertex coordinates in UTM projection and the

area computed on the ellipsoid using geodetic coordinates of the

four equivalent vertices. However, the straight line in UTM projection

with a length of almost 250 km (for the largest of the verification

figures) is in the general case different from the projection of the

geodesic - in this case, the maximum displacement between the two

is considerable, and varies significantly between the easterly

(11.3 meters) and westerly (28.9 meters) edges. If the geodesic

edges connecting the vertices on the ellipsoid are projected

back to the UTM plane (as a sufficiently dense array of vertices),

and the area is recomputed, it changes by approximately 1 in 10000 -

quite a bit above the precision level of the ellipsoidal area

computation claimed by both methods.

Numerical and timing tests performed and presented here use a data

object derived from the world coastlines coverage of the

Digital Chart of the World (see References, DCW, 1992).

It provides multiple "layers" of general-purpose geographical data,

commensurate in the precision and density with that of a 1:1 million

paper map, using angular geographic coordinates in 5 degree "tiles"

on the WGS 84 ellipsoid.

Before the DCW data could be used, however, numerous topological

inconsistencies - occurring primarily on the DCW tile edges - had

to be detected and removed. The resulting data set consists of

1.3 million vertices, in 27.3 thousand boundary rings - the largest

of them encompassing all of the landmass of Europe, Asia and Africa.

As a Hipparchus canonical 2-dimensional data set, the object size is

slightly over 12 MB. (Raw coordinate data - at 8 bytes per point -

takes approximately 11 MB of that).

The average coastline boundary segment is slightly under one kilometer,

and less than 1.5% of the segments exceed 3.5 kilometers in length.

It is thus safe to assume that the boundary segments - computationally

represented by segments of great circles on a conformal sphere - are

coincident with the projection of the ellipsoid geodesic connecting

the two boundary vertices. (For objects with long boundary segments

Hipparchus vector algebra offers a fast yet highly precise approximation

of the geodesic line computation as a mid-point between two points:

one on the direct and the other on the inverse vertical intersection.

(Details of these and other vector-algebra based geodetic techniques

can be found in an online

Hipparchus Tutorial).

By simply inverting the order of boundary vertices in each ring,

we can produce two conjugate objects: one representing the continental

landmasses and islands, and the other representing the global Ocean.

Both objects are represented in a global Voronoi grid of 2432 cells.

The area of both objects has been calculated, with an obvious expectation

that their perimeters (a natural by-product of the computation) will be

the same, and that the sum of their areas will be equal to the total

planetary surface.

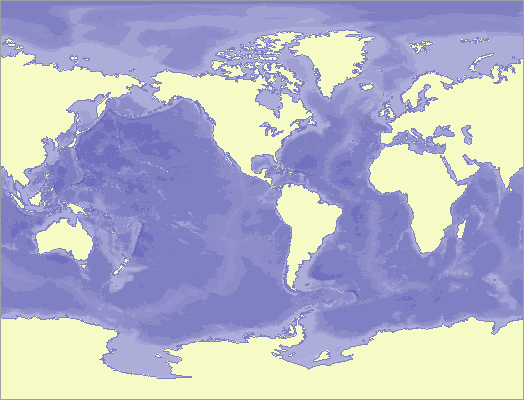

Figure 3: Seven Seas - A Geometry Object

The area computation program initialization consists of the

instantiation of the Voronoi grid as a memory-resident object and of

the steps necessary to establish the memory-mapping access to the

files containing the two objects. The area computation is packaged

as a Hipparchus Library function named h7_RsetAreaPerimeter();

its parameters are four pointers to given data: to the Voronoi grid

descriptor, some workspace, ellipsoid geometry parameters, and header

data of the object for which the area is required; plus two pointers

to returned values: the area and the perimeter.

The results presented here have been obtained using the code compiled

with the GNU C compiler V.2.95.2, carried out on a 400 MHz Pentium II under

Linux kernel 2.2.14. (Performance under NT was only marginally slower).

Ellipsoid: WGS 84, a=6378137.0e0, b=6356752.3141e0

The 2432 element cell-array area initialization took 0.19 seconds

and produced the following values (square meters):

Ellipsoid area: 510065621716336.1

Total area of all cells: 510065575723515.5

Difference: 45992820.6

Relative difference (one in): 11090113.0

Area computation for both objects took 3.94 seconds (each),

and produced the following values (square meters, meters):

Landmass area: 150998900960532.0, perimeter: 1249923047.850

Oceans area: 359070890924373.1, perimeter: 1249923047.850

Ellipsoid area: 510065621716336.1

Landmass + Oceans 510069791884905.1

Difference: 4170168569.0

Relative difference (one in): 122313.0

Conclusions

The following conclusions seem to be justified:

-

Computation of the ellipsoid cell areas using local mean curvature at

the cell center produced the results which are within one in 11 million

of the total ellipsoid surface area. For the grid and objects

as examined in the example, this is two orders of magnitude better

than the results of the object area computation, and thus adequate.

-

Computation of two very large planetary complement objects produces

results which are within one in 122 thousand of the total ellipsoid

surface area. The obtained level of accuracy is a result of a combination

of factors; the major one probably the inevitable rounding error in a

very large number of (over 1.3 million) of relatively narrow triangles.

The obtained accuracy compares favorably with that in many operational

systems which compute the areas in the plane - at the outset a significant

departure from the true object geometry.

-

The very short time needed to carry out the area computations of large objects

makes it practical to compute it only as and when this information is

required. This facilitates the system design in which the area of a

global object of any size and/or shape is not treated as an independent

attribute, but rather as only one in a repertoire of measures that can

be derived from its canonical geometry definition.

References

-

______, Digital Chart of the World (CD publication),

United States Defense Mapping Agency, Fairfax, VA 22031-2137. July 1992.

-

Bomford, G. Geodesy, London, Oxford University Press, 1975 ed.

-

Bowyer, A and Woodwark, J. A programmer's geometry, Sevenoaks, Butterworths, 1983.

-

Jordan, Eggert and Kneissl, Handbuch der Vermessungskunde (Band IV: Mathematische Geodaesie),

10th ed. Metzlersche Verlag., Stuttgart, 1959

-

Kimerling, A. J.Area Computation from Geodetic Coordinates on the Spheroid,

Surveying and Mapping, Vol. 44, No. 4, 1984, 343-51.

...

|